Hidden Figures: Below-Ground Carvings on Gravestones from the Early 1800s

Twelfth in a series of Occasional Papers about Eastern Cemetery in Portland, Maine

by Ron Romano

© September 2023

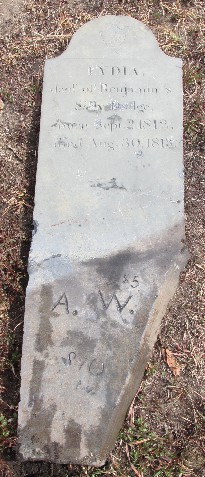

Photo courtesy of Janet Alexander

Photo courtesy of Janet Alexander

When gravestones are freed from the ground in order to straighten or repair them, we sometimes find crudely carved markings on the below-ground portion of the stone. Not meant to be seen when the stone is properly placed, these are often referred to as “carver practice marks.” While that may be an accurate description for some stones, an increasing number of stones are discovered with underground marks that appear to have served some purpose. To date, the Spirits Alive conservation crew has documented more than 40 such stones at Portland's Eastern Cemetery, but similarly marked gravestones have also been found at seven other cemeteries in the area. This paper examines these hidden figures—most of which are on stones produced from 1800 to 1830—and shines a light on three stonecutting brothers who are connected to the majority of them.

Contents

- The First Set of Letters

- The Anatomy of a Slate Gravemarker

- True Practice Marks

- Prices and Numbers

- More Initials

- The Washburn – Adams Connection

- Ira Washburn (1788 – 1836[?])

- Alvan Washburn (1792 – 1868)

- Elias Washburn (1796 – 1826)

- A Curiosity

- Another Curiosity

- The Wrap-up

- Hidden Figures Details (table)

- References

Note: Most of the photos in this paper are from Janet Alexander and other members of the Spirits Alive board and conservation crew: Diane Brakeley, Holly Doggett, and Martha Zimicki. Photos from others are indicated in the captions. My thanks to all who have shared their pictures for this paper!

The First Set of Letters

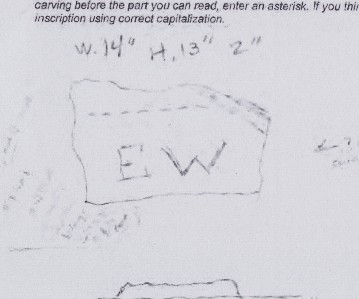

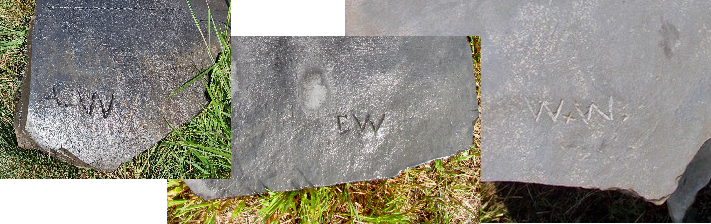

In 2011 while working on a comprehensive project to document gravestone inscriptions at Eastern Cemetery, Martha Zimicki and her team from the cemetery’s friends group, Spirits Alive, discovered a fairly large slate fragment with the letters “E W” crudely carved on it. The fragment was at the plot assigned to Elizabeth Kimball, who died in 1816 at age 6. Nearby, an intact stone was found for the Watts family. The team assumed that the “E W” represented someone named Watts and that at some point in past 200 years this rustic gravestone had been moved from its original location. They measured it, drew a picture of it for the transcription project (photo below), and then reburied it where they thought it belonged—at the Watts plot.

Detail of the transcription form created for Elizabeth Kimball’s gravestone.

The Anatomy of a Slate Gravemarker

Eastern Cemetery (established 1668) has hundreds of gravestones made of gray slate. From the early 1700s to the mid-1800s it was the region’s stone of choice for marking graves. It was plentiful and relatively easy to hand-carve but strong enough to withstand the harmful effects of the weather extremes that marble and other “softer” stone types just cannot. One key source was the South Shore of Boston, which supplied slate to stone masons and gravestone makers there as well as New Hampshire and Maine. The quarried slate would be cut into large blocks, then cleaved into “slices” about two inches thick—the typical thickness of a colonial era gravestone. Local stonecutters would then shape and size the stone and smooth its surfaces to ready it for decorating. To ensure that the slate would stay in position once placed at the gravesite, the stonecutter kept the slabs tall and narrow. The top 2/3 (that is, the portion visible to passersby once in place) would be decorated and inscribed. The bottom 1/3 would be left unfinished since it was to be buried and out of view.

Having a large portion of the slab underground provided stability to the marker and helped prevent—or at least delay—it from tilting or falling. When slates are pulled from the ground during conservation, we find an interesting array of shapes on the unfinished, hidden portion of them.

While it would have been obvious to the men placing these stones on graves that the rough portion of the marker was to be out of sight, many stonecutters carved a “burial line” at the bottom of the marker to be used as a guide. Today, after years of being jostled by the wintertime freeze/thaw cycles of the ground or by being exposed above grade by the natural settling of the dirt that surrounds them, many old slates reveal their burial lines. One just needs to get down on the ground and take a careful look! It’s below the burial lines that we find the hidden figures.

The blue line on this gravestone for Abigail Burnham shows the separation between the top (finished) and bottom (unfinished) portions of a typical slate. Note how large the bottom portion is, providing stability to the marker once it was properly set on the grave.

A marker from 1824 shows the burial line carved to guide those placing the marker on the grave. The staining on this marker helps to reveal the burial line; more often they are faintly carved and hard to see. Author photo.

True Practice Marks

Above: Detail of Abigail Burnham’s marker. The top of the stone was finished by Bartlett Adams; these markings are likely the work of one of the apprentices or shop boys working for him.

A few markers unearthed at Eastern Cemetery do have true carver practice marks. The stone shown above for Abigail Burnham, who died in 1798 at the age of 55, provides an example. Two dozen characters are scattered over the bottom portion of the marker. While some random letters are evident, other figures scratched on any which way are also present. This marker is attributed to Bartlett Adams, Portland’s first stonecutter, who was an accomplished carver and would not have needed to practice his letters for this stone. This suggests that an apprentice or shop boy was responsible for the figures.

First Parish Church Cemetery in Brunswick was established in 1735. It has a nice collection of Boston-made gravestones from the 18th century and 40 markers from the Bartlett Adams shop in Portland (operating from 1800 to 1828). The small graveyard is in need of some care, and it is a challenge to find an early marker that isn’t tipping, broken, on the ground, or heavily covered in lichen. The back left corner has two dozen stones and stone fragments placed flat on the ground along the fence, presumably fallen or broken markers that have been removed from other areas of the site.1 Most are not identifiable to any specific person. Recently, while designing a tour there, I found a slate fragment that has true practice marks. In this case we see the first 5 letters of the alphabet in a single line. It’s a great specimen just as it is, though I’d have done cartwheels through the graveyard if I’d found the entire alphabet cut onto this slate.

A slate fragment at Brunswick’s First Parish Church Cemetery. Author photo.

Back at Eastern Cemetery, another interesting fragment was found in 2018 that we cannot link to any specific person. Shown below, there are at least 20 characters on this one. In addition to discernible but seemingly random letters, a close look reveals both a dollar sign and 2 ampersands. In the photo, Martha points to the lightly carved “$.” One of the ampersands is to its right under the “J” and the other is lower left, the “&” partially hidden by her hand. Also of note on this piece is that lettering guidelines were etched onto the surface (seen above and below the top two sets of characters).

Stonecutters sometimes employed these faint lines to keep their letters straight as they cut the inscription across the surface of the stone. They may also have used charcoal or some other substance, all of which could be rubbed out before the stone left the shop.2

Prices and Numbers

Four markers have been found with prices carved onto them. A fragment discovered at Yarmouth’s Hillside Cemetery shows a clear “$11” as the cost of the original stone.3 We don’t know who it belonged to or how large the original stone was. This fragment was recently found near the front gate and is believed to have been unearthed when the fence along the main road was replaced earlier this year.4

Just under the burial line, note the price of $11. This slate fragment at Yarmouth’s Hillside Cemetery was photographed by Katie Worthing.

Others in this category are:

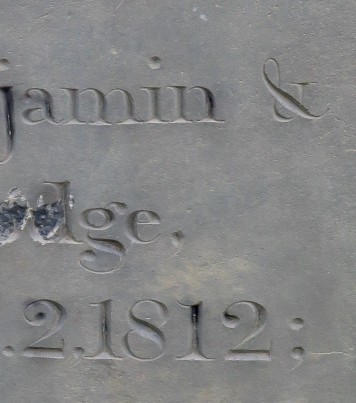

- Lydia Dodge, who died in 1813 just 3 days before her first birthday. Her marker at Eastern Cemetery was dangerously tilting so it was carefully dug up to be reset. Hidden below we found “$5—” and other marks. The photos of her stone are on the title page.

- Samuel Bacon, who died in 1815 in North Yarmouth at the age of 6. I found his stone lying on the ground at Walnut Hill Cemetery while mapping the route for a tour I’d been asked to do there. I noticed that the price of “$5.25” was carved on the lower right. The stone has since been returned to its original upright position.

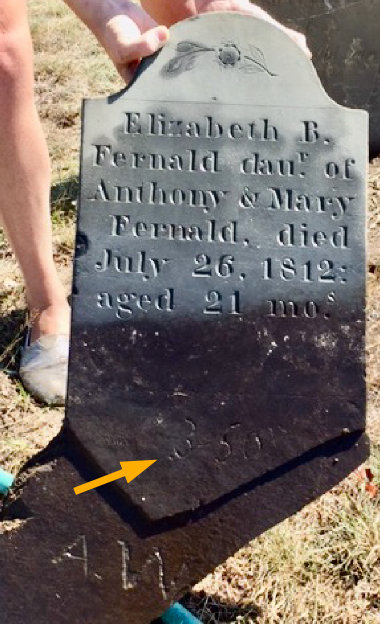

- Elizabeth Fernald, who died in 1812 at 21 months. Her marker was pulled up and reset during our 2016 conservation season at Eastern Cemetery. Though the hidden figures do not include a dollar sign, “3.50” appears to have been the price of her small gravestone.

Those of us who study old gravestones believe that stonecutters likely kept a small stock of decorated—but uninscribed—markers available in their shops for people to see. Customers could choose the size and design they liked, and the stonecutter would then add the lettering details to the stone. The few gravemarkers found with hidden prices carved on them support that notion; there would be no need to carve a price onto a stone after it was purchased.

Imagine it is the fall of 1812: Anthony and Mary Fernald are visiting the stone shop at the corner of Federal and Fish (now Exchange) Streets in Portland. They see a small slate marker decorated with a simple flower and branch for $3.50 and decide it will be the perfect memorial for their daughter Elizabeth, who had died that summer before reaching her second birthday.

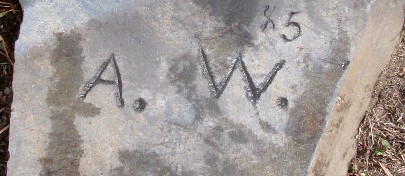

Elizabeth Fernald’s slate marker shows the price of $3.50 centered below the “21” of the bottom line. Note too the initials A. W. at the very bottom of the unfinished portion of the stone.

Other numbers are found on other stones. They’re probably intentional rather than practice marks but their meanings have been lost to time.

- Lucretia Loring, who died in 1831 at the age of 9 months, has a stone at Eastern Cemetery with “2 + 1” carved on it.

- The side-by-side stones for wife and husband Joanna and Joseph Delano both have hidden numbers. Joanna’s 1845 marker has “5” and Joseph’s 1831 marker has “49” (and it’s not his age, since he died when he was in his fifties).

- Jane Harmon, who died in Buxton in 1832 at age 7, has a finely carved (versus crudely etched) “210” centered on the stone just below the burial line. Was this the weight of the stone? A plot number at Woodlawn Cemetery? Perhaps it was a stock inventory number. I just don’t know.

More Initials

A few years after the 2011 transcription project discovery, another marker was pulled from the ground at Eastern Cemetery that had the same crudely carved “E W” on its hidden area. But this time the gravestone was intact and the deceased’s name was known: Abel Baker, who’d died in 1812. It became clear that the fragment etched with “E W” discovered in 2011 was not a stone for the Watts family, but for someone who had worked on the stone. And the obvious choice was Elias Washburn, who I knew had been in his uncle Bartlett’s stone shop around that time. But… I’d earlier attributed the Abel Baker stone to Elias’s older brother Alvan, and I was confident in that attribution. Having spent countless hours over many years studying the (above-ground) work of Adams and his nephews, I thought I could sort these stones by carver based on the above ground features. So what was going on?

The collection of hidden figures and initials has continued to build each year. We are no longer surprised—just delighted—when another stone is pulled from the ground with an “E W” or “A W” etched below grade. We find that some of these initials were cut using a period (that is, “A.W.” instead of “A W”), but not always. Along the way we’ve also recorded a few “W + W” etchings. If these crudely carved initials were a means to identify the man who worked on the stone, “W + W” suggests both Elias and Alvan had some hand in making them.

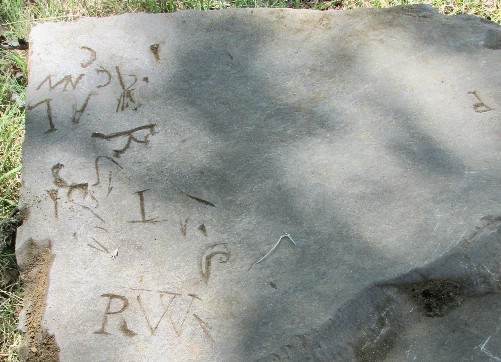

Left to right: Alvan Washburn’s initials on the 1814 marker for Barzillai Delano Taylor, Elias Washburn’s initials on an 1813 stone for Susan Wilson, and the “W+W” on a shared 1818 marker for Jeremiah and Joanna Berry. All three stones are at Eastern Cemetery.

Ira Washburn’s initials on the Catherine Tate marker from 1818 at Stroudwater Burying Ground.

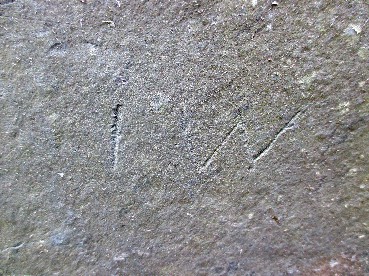

In 2016, I surveyed the Stroudwater Burying Ground for a tour I was planning for the Tate House Museum, and noticed a rustic “W” at the bottom of the large slate marker for Catherine Tate, who died in 1818. The bottom few inches of her stone had lifted from the ground revealing the hidden letter. But a closer look revealed that this etching wasn’t a single letter but “I W” instead.5 In context with the other initials being unearthed at Eastern Cemetery, I knew who this was. Now, with almost 20 markers found with the letters EW, AW, and IW on them, there is no question that these are the initials of three brothers: Elias, Alvan, and Ira Washburn.

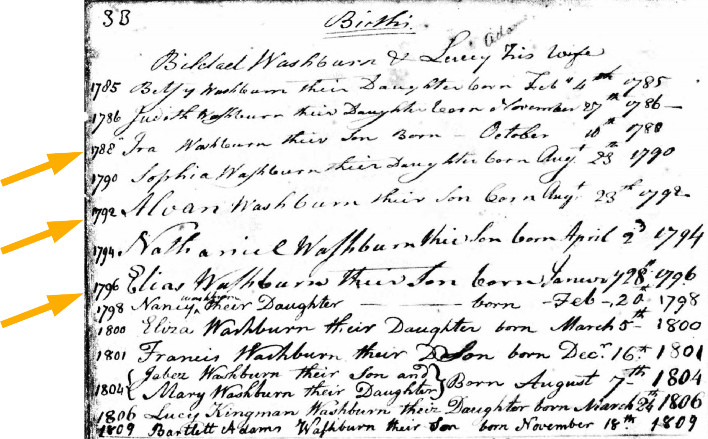

The Washburn-Adams Connection

The brothers were born in Kingston, Massachusetts, to stonecutter Bildad Washburn and Lucy Adams, who married in 1784. Lucy was an older sister of Bartlett Adams; their family was also from Kingston. Bartlett was just 8 years old at the time of their marriage. By the time Bartlett reached his mid-teens, he became an apprentice in Bildad’s shop and there learned the craft of stonecutting from his talented brother-in-law. Lucy was busy caring for the 15 children she delivered over 25 years. Ira was third in line, born 1788, and Alvan was fifth in line, born 1792. Their uncle Bartlett would have known them as young children, as he was likely living in their home while apprenticing. Elias was seventh in line, born in January 1796. Though Bartlett was probably still in Kingston at the time of Elias’s birth, that was the year he had progressed from apprentice to journeyman and left the Washburn shop to fine-tune his skills at another shop in Quincy, Massachusetts.6

A page from the vital records of Kingston, Massachusetts

My book, Early Gravestones in Southern Maine, focuses mainly on Bartlett’s life and work once he moved to Portland.

Fans of the story of Bartlett Adams and the history of Eastern Cemetery know that in 1800 Bartlett made his way to Portland, where no other stonecutter was yet established. For nearly three decades he owned the only such business in the area. His success is evidenced by the 2,000 or more gravestones produced in his shop and surviving today in over 200 cemeteries in the region. Of course he didn’t make all those stones on his own.

Apprentices and talented, seasoned stonecutters worked with him over the years. Among them were his three nephews.

Ira Washburn (1788 – 1836[?])

Ira’s story is the most challenging to tell. Few records are found for him, and most of those have him living in Massachusetts. Researcher Jim Blachowicz believes that Ira married in Charlestown in 1817 around the time he was working in the stone shop operated there by Richard Adams (Bartlett’s younger brother). According to Boston tax records and city directories from 1818 to 1822, Ira was a journeyman stonecutter. Blachowicz suggests that Ira did not leave behind a collection of markers we can attribute to him. But Jim studies the visible lettering and decorations on markers; this paper considers the hidden figures on them, and it appears that Ira Washburn did indeed touch a few stones here in Maine.

Charity Thomes’s 1823 marker lettered by Bartlett Adams. The stone is initialed “I W” and may have been decorated by Ira Washburn.

Joseph Plumer died in 1802 at the age of 31 years.7 The above-ground portion of his marker was decorated and lettered by Alpheus Cary, an accomplished carver who joined Bartlett Adams’s shop in 1806 for just a couple of years. Below ground we find the initials “I W” along with what appears to be the number 11. Assuming that the stone was among the first Cary worked on in 1806, Ira Washburn would have been 17 or 18 and certainly could have been in Portland working in his uncle’s shop. Had he been the one who cut the stone to size and shaped it so that Alpheus Cary could then put on the finishing touches of the urn and inscription? If so, perhaps he’d carved his initials onto the bottom of the stone. Working in the shop in the capacity of preparing the stones—sizing the slab, cutting the shape and smoothing the surface—was an important job. It meant that the finisher, the trained stonecutter, could spend his time decorating and lettering the stone. If Ira’s role was to prep the stones, it helps to explain why Jim Blachowicz has not been able to find a group of gravemarkers to assign to him.

While working at the Stroudwater Burying Ground Janet Alexander found a second gravestone with the initials “I W” on it. It was for Charity Thomes, who died in 182three at age 72. I had (confidently!) attributed the lettering on that stone to Bartlett Adams, but I had not been able to nail down the urn’s carver. The decorative elements differ too much from the more common designs I know were produced in his shop. So now I wonder… Could this be the work of the journeyman stonecutter Ira?

As noted, records are just not good for the eldest of the three stonecutting brothers. If Ira was responsible for the three gravemarkers with “I W” discovered on them, it suggests he worked with stone for at least two decades, and that he came north to Portland and worked in his uncle’s shop on more than one occasion.

Alvan Washburn (1792 – 1868)

Alvan Washburn was working in Bartlett’s shop in his teens as an apprentice, as early as 1809.8 Bartlett must have been impressed with Alvan’s work because he turned the shop over to Alvan during the War of 1812. Newspaper advertisements from the period show that Alvan operated the shop from the fall of 1812 to the spring of 1814. Bartlett had left Portland for New Gloucester, about 25 miles inland, where he had a 100 acre farm and orchard. Alvan produced an impressive collection of markers during his time running the business. He primarily decorated his stones with urns that he’d learned from his uncle; there are a few cases where we find that he copied one of Bartlett’s signature urns but made it his own by adding decorative elements Bartlett did not use.

With respect to his lettering and numbering, Alvan had a distinctive backward leaning ampersand (photo below) that makes his work easier to identify. He also seems to have struggled a bit with the number “2.” Again and again I find subtle inconsistencies in his rendering of that particular character when repeated on the same stone. In the example shown, note how the upper loop of the second 2 is much more open than the first, and the first’s lower horizontal stroke is at a bit of a downward pitch. All in all, Alvan’s body of work shows that he was a talented stonecutter who had learned well from his uncle.

Alvan had just turned 20 when he took over his uncle’s shop and was almost 22 when Bartlett returned. He must have gained confidence during his brief but successful time in Portland. Shortly after Bartlett’s return Alvan made his way to the midwest, marrying along the way. Once in Ohio, he opened a stone business of his own and worked in the industry for many more years. He died in 1868 at age 76.

I’ve attributed about 60 markers to Alvan Washburn during his time in the Portland shop, though the more I study the Eastern Cemetery gravestones from the 1810s, the more I think I may be undercounting his work. He had a couple of urns that I consider to be his signature urns, but he also created a limited collection of simple flowered branches.

While discussing prices and numbers above, I took us back to 1812, imagining Anthony and Mary Fernald visiting Bartlett Adams’s shop—which was then in the hands of Alvan Washburn—to pick out a stone for their daughter. Not only does the marker they selected have the price, it has the initials “A W” crudely carved (and twice the size of the inscription’s letters). The design of the stone is Alvan’s flowered branch, a simple but charming decoration quite appropriate for a child. It’s clear that the Fernalds bought two markers that day, as another one of the same size with the same flower (sans branch) and same lettering is on the plot next to Elizabeth’s. That marker is for their first daughter. She was Elizabeth the first, born in 1805 and died in 1807; Elizabeth the second was born in 1810 and died 1812.9 Our conservation crew hasn’t worked on Elizabeth the first’s stone, but I suspect that if we ever do, we’ll find similar hidden markings.

The two markers for the Fernald daughters, purchased in 1812 and nearly identical in design and lettering by their maker Alvan Washburn.

So far, there are six markers with the hidden initials “A W” known. Five of them are at Eastern Cemetery, but one is 50 miles due north of Portland in the town of Sumner’s Hill Cemetery. That stone is for John Bisbe (Bisbee), who died in 1816 at age 13. Coincidentally, Bisbe’s stone also features Alvan’s simple flowered branch design.

Back at Eastern Cemetery, the slate marker for Martha Chamberlain, who died in 1811 at age 2, is decorated with Alvan’s flower and branch too. When the stone was pulled from the ground to reset it, we found a practice flower at the bottom!

Above left: Alvan Washburn’s simple flowered branch design on the Fernald stone. Right: The practice flower on Martha Chamberlain’s stone from 1811.

Elias Washburn (1796 – 1826)

The youngest brother of the stonecutting trio was Elias, whose relatively short life seems to have been filled with adventures. During the War of 1812 he obtained a Seamen’s Protection Certificate, a document that served as identification of nationality for seamen (and citizens) traveling abroad. Elias was in Salem, Massachusetts, at the time. He was 16 and described as 5 and 1/2 feet tall with fair skin and light eyes. He had scars on his left arm. I don’t know if he ever actually travelled abroad, but his brother Alvan had taken over Bartlett’s shop around the same time and I think he may have called upon Elias to come to Portland to help him keep things going. At least six markers I’ve attributed to Alvan have the hidden figures “E W” carved on them. Was Elias marking the stones he had prepared for Alvan?

When Bartlett Adams returned to his shop in 1815, Alvan headed west and Elias went back to Massachusetts. Early in the spring of 1817, 21-year-old Elias impregnated 15-year-old Lydia Allen. She was about 3 months along when they married in June in Malden; shortly after the wedding they moved to Portland. It may not have been that unusual in the early 1800s for young people to have premarital relations, but the speedy move to Portland shortly after marriage suggests that it would have given them a fresh start and the opportunity to hide the fact that she was already pregnant when they married. In any event, Lydia delivered their first child, Allen Jerome Washburn, in Portland that November, 5 months after they’d wed.

Portland was also a good place to land since Elias’s uncle Bartlett still had a thriving stone business on Federal Street. Elias had spent time there with his older brother Alvan, so it was probably an easy transition back to stonework for him and his uncle. Bartlett had big plans though: He was going to temporarily relocate to Boston and open a new shop in Charlestown with his younger brother Richard. With Alvan already in Ohio, Elias was probably his next best choice. Bartlett had an attorney draw up a letter of agreement with Elias in October of 1817, and no doubt spent the next 6 months training Elias in the running of the shop.

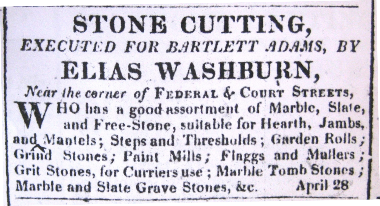

On April 28, 1818, a new series of advertisements appeared in the Portland Eastern Argus newspaper, announcing that Elias Washburn was cutting stone “for Bartlett Adams.” Note that when Alvan ran his first ad in 1812, the business relationship was expressed differently: Alvan had “taken the shop and stock of Bartlett Adams…” Now, Elias was cutting stone “for” his uncle, a clear sign that Bartlett fully intended to come back to Portland.

-

STONE CUTTING, EXECUTED FOR BARTLETT ADAMS, BY ELIAS WASHBURN, Near the corner of Federal & Court Streets, WHO has a good assortment of Marble, Slate, and Free-Stone, suitable for Hearth, Jambs, and Mantels; Steps and Thresholds; Garden Rolls; Grind Stones; Paint Mills; Flaggs and Mullers; Grit Stones, for Curriers use; Marble Tomb Stones; Marble and Slate Grave Stones, &c. April 28

Elias had stonecutting in his blood but his work was far less precise than either that of his father Bildad or his uncle Bartlett. Like his older brother Alvan, Elias copied some of the basic designs from his uncle but made them his own. And like his older brother, he also had a “signature urn,” a design that I can tie to him for its unique decorative elements. I’ve found over 100 markers decorated with an urn that has a single swag across the middle. It sometimes resembles a chain, but of course a funerary urn would not have a chain, so it must just have been Elias’s artistic flair. All but a handful of these were produced from 1818 to 1821, exactly matching the time period that Elias ran the shop for his uncle. But unlike his uncle or older brother, Elias was a sloppy carver, with uneven or messy lines, imprecise cuttings, and errors in spacing and lettering frequently found. Compare the 4 flutes on Elias’s urn to the seven carved by his uncle (photos below). The decorative lines on the stem of Elias’s urn are also sloppy and uneven.

Elias Washburn Urn

Bartlett Adams Urn Flutes

Most of the hidden figures with Elias’s initials are for stones that were finished by Alvan. But there is a very interesting pattern found for stones that were finished by Elias: 4 markers at Eastern Cemetery that have the hidden figures “W + W” happen to be decorated with Elias’s signature urn and lettering. So, another mystery. If Alvan was in the midwest, could these two initials be for Elias and his older brother Ira?

Recall that Catherine Tate’s 1818 marker at Stroudwater has the initials “I W” on it, which I believe is for Ira Washburn and suggest that it gives some proof he was briefly working in the Portland shop at that time. It’s worth noting that 4 of the 5 markers found with the initials “W + W” were for deaths that occurred in 1818 or 1819. The last is tied to the others: While it is for a death that was in 1816, the stone was made for Henry Colley, and it’s his brother Jacob who died in 1818 and is memorialized on one of the 4 other markers in this grouping. It’s very easy to see that the Colley family purchased two stones at the same time (in 1818), one for Henry and one for Jacob, just as the Fernalds had done in 1812 for their daughters named Elizabeth.

In 1819, Lydia delivered another son, Adams Monroe Washburn. In 1821, the couple’s third child arrived, a daughter named Lucy (after Elias’s mother Lucy Adams). Around the same time Bartlett and Richard closed the Charlestown shop and Bartlett brought his family back to Portland. Taking back his own business did not go smoothly. He tried to get his nephew to return the contract that had enabled Elias to transact business on Bartlett’s behalf, but Elias did not comply. Instead, he headed up the coast of Maine to Eastport—close to the Canadian border—where he left behind a small collection of markers decorated with his signature urn.10 Finally, at the end of 1822, Bartlett published a notice in the newspaper declaring that because of Elias’s failure to return the contract they’d had in place since 1817, the “instrument [is now] null and void.”

Elias took his family back to Massachusetts where he continued work as a stonecutter. Lydia delivered their fourth child, Elias Jr., in 1825, but he died before reaching his first birthday, and Elias soon followed. He passed in 1826 at the age of 30.

A Curiosity

Sarah Haskell died in 1822 at the age of 2. Her large slate marker at Eastern Cemetery was lettered by Bartlett Adams, but it features an urn that was carved by Elias. It was not unusual for more than one man to work on a stone. With distinct phases of preparing the stone, decorating the top, and lettering the stone, we’d expect at least two—and sometimes three—men to be involved. The timing works for Sarah’s stone, as Elias was in the shop until 1821 and could have carved the urn and left the inscription panel blank for future use. By the time Sarah’s parents purchased the marker, Bartlett was back in the shop and cut the letters onto the blank panel.

Having one man decorate and another man letter the same stone is not what makes this a curiosity. Instead, this is the only marker found that has hidden markings on the edge of the stone. It’s easier to carve a smooth flat surface; chiseling onto the unfinished stone edge would have been more challenging. The hidden markings along the bottom edge of the Haskell stone are a date: Aug. 24, 1815. My guess is that a new supply of slate had arrived at the shop—perhaps stacked one atop another—and the date was carved on the exposed edge of one of them to help keep track of inventory. It makes sense, but it is just a guess.

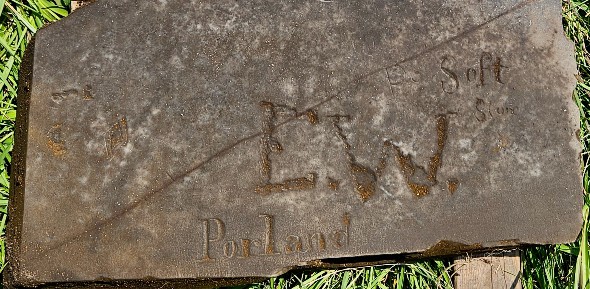

The etched date is not the only thing that makes the Haskell marker special. On the flat surface of the underground portion of the stone a huge “E. W.” is hard to miss.

Better still is the carving just below his initials. It’s “Porland,” a misspelling of Portland. That error leads me to think that it was Elias who had marked up the bottom of this stone, since his work was frequently below par.

Detail of the below-ground section of the Haskell marker.

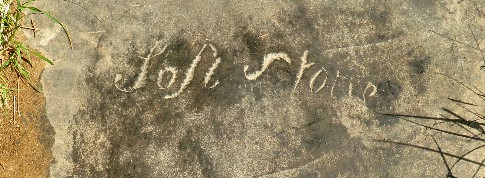

Finally, the words “Soft Stone” appear just up and to the right of the initials. This is not the first time we’ve found such a marking. It was probably intended to advise the one who would do the decorative and lettering work that the stone was particularly easy to carve.

The Haskell stone as it was pulled from the ground.

Others in this group are:

- Abel Baker’s 1812 marker has “Soft”

- Sarah Cammett’s 1814 marker has “Hd” (for “hard”?)

- The unidentified fragment at First Parish Church Cemetery (Brunswick) has “Soft Stone” (photo below)

- The unidentified fragment at Hillside Cemetery (Yarmouth) has “Soft”

The fragment in Brunswick.

Another Curiosity

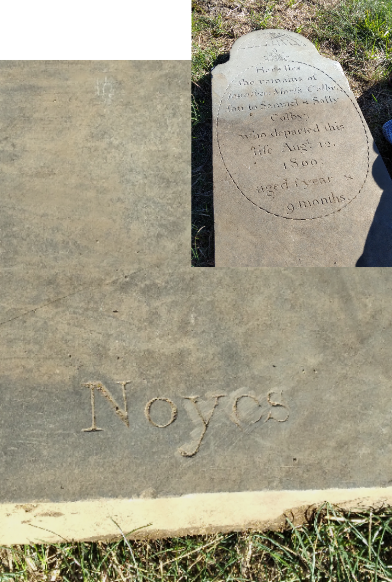

In August of 1800, just 4 weeks before Bartlett Adams opened his stone shop in Portland, 1-year-old Jonathan Morss Colby died. Until Bartlett’s shop launched that September, the nearest stone shops were in Boston, so there was a pent-up demand for gravestones in Portland. In his first few years in business, he made at least 60 stones for people who were buried at Eastern Cemetery before he’d arrived (and whose graves had likely been marked with a piece of field stone found by the family or a wooden marker, if at all). The furthest-backdated stone in Bartlett’s hand is for Mary Noyes, who had passed in 1772, 28 years before the shop opened. Bartlett carved a beautiful urn on her marker and inscribed her stone with his best lettering, then matched all of it on the stone for her husband Joseph Noyes, whose death was in 1795—also well before Bartlett had moved to town. But in addition to meeting the demand for stones for those long-past deaths, Bartlett also had stones to make for the people dying concurrent to his presence in town. Families of at least 17 people who died in 1800 visited the shop for an Adams-made gravestone; among them were Samuel and Sally Colby, Jonathan’s parents, and it’s his stone that is the curiosity.

Inset: The stone for Jonathan Colby as it was pulled from the ground. Main photo: The Noyes name neatly carved at the bottom of the Colby stone.

On the below-ground portion of Jonathan’s marker we find the name “Noyes” neatly lettered, and though there are only those five letters to examine they seem to be in Bartlett’s hand. The Noyes family is well represented at Eastern Cemetery; nearly fifty burial records with that surname are documented.11 In his first decade, Bartlett carved at least nine markers for members of the Noyes family (including Mary’s and Joseph’s). My brief look at Jonathan Colby’s family tree yielded no obvious links to the Noyes family. The lettering is not crude, but finished. It makes me wonder if the stone that ended up on Jonathan Colby’s grave may originally have been intended for the Noyes family.

The Wrap-up

Fifty-one markers and fragments were analyzed for this paper. Forty-two are located at Eastern Cemetery, three are at Stroudwater Burying Ground, and the remaining are found at different cemeteries in the region. The chart at the end of this paper provides more details.

Slate predominates; only three in the study are marble. All but a few stones are tied to the shops of Bartlett Adams and his successors, with 27 of them linked to the Washburn brothers (either by their finished decorations and lettering or by their hidden figures).

One of three marble markers with initials. This one is shared by four siblings in the Frothingham family, who died between 1793 and 1813. The stone is at Eastern Cemetery.

Though the study size is small, it’s clear that many of the hidden figures on these gravemarkers actually served a purpose rather than simply being random practice marks. We can also safely say that the initials found were not intended to serve as the signature of the man who decorated the stone. Not only are they crudely done and found below ground level, they are limited to three brothers. Had it been common practice to initial one’s work, we would surely by now have unearthed initials from the others in the Adams shop: Richard Adams, Alpheus Cary, Abel Davis, Robert Hope, Francis Ilsley, and others. Marking stones with initials seems to have been a Washburn thing.

The “A. W.” found below ground on the Frothingham stone.

Having the only stone shop in the area for almost 3 decades, Bartlett Adams didn’t need to sign his markers. He had no local competition! When he was a journeyman in Massachusetts he did sign many markers; there he was in a competitive environment alongside other journeymen cutters who were working towards opening their own shops one day. In our area, stonecutters did not sign their markers until the mid-1800s, when marble had replaced slate, many more stonecutters were at work, and the competition for business was strong. Instead of hiding signatures below ground, the mid-century marble workers signed their work in the visible lower right corner (just as artists do on paintings), allowing passersby to see firsthand their carving abilities.

As noted above, only a few of the stones that hold the various Washburn initials were finished by the one whose initials appear below ground. In particular, those initialed “E W” tend to have been finished by Alvan, and those initialed “W + W” were finished by Elias. Alvan’s initials appear on stones that he also finished, but those markers were for deaths that occurred when he was running the shop for his uncle (doing decorative work), not when he was an apprentice (doing prep work). There’s good reason to assume that Alvan’s work as apprentice from 1809 to 1812 included preparing the stones for Bartlett to finish and that he carved his initials onto the bottom of the markers he’d sized and shaped—some of which he would later decorate as proprietor of the shop.

There is one outlier in this study. A Boston-made stone for Peter Walton, who died in 1733, is among the earliest surviving gravemarkers at Eastern Cemetery. During resetting, it was found to have some true practice marks below ground, consisting of a letter “T” and some stray figures. Otherwise, we find that it was the Adams shop that is primarily responsible for these interesting markers.

Finally, as the Spirits Alive conservation crew continues its fine work—now under the direction of Janet Alexander and Dave Smith—I expect more stones will reveal their hidden figures and help answer some of the questions that remain about their meanings and purpose. For now, we get to enjoy discovering these interesting marks and appreciating what’s found below ground level.

THE END

This stone at Eastern Cemetery is for Huldah Ann Warren, who died in 1826 at age 15. The double “X” figure at the bottom of her marker served a purpose. It matches another one on the large stone slotted base in which the marker was set. The Adams shop chiseled these marks as alignment guides for the men who originally placed the stone on Huldah’s grave. Two hundred years later our conservation crew was also able to use the markings to reset the stone at the gravesite.

Hidden Figures Details

| Primary Mark(s) | Notes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1815 | Bacon | Samuel H. | Walnut Hill - | - | -$5.90 | Elias Washburn’s urn and lettering |

| 1812 | Baker | Abel | Eastern | E W | Soft | Alvan Washburn’s urn and lettering |

| 1818 | Berry | Joanna & Jeremiah (1816) (spouses) | Eastern | W + W | 5 — | This is a double-top shared marker featuring Elias Washburn’s urn and lettering. |

| 1813 | Bisbe (Bisbee) | John | Sumner Hill - Sumner | A. W. | - | Alvan Washburn’s flowered branch and lettering |

| 1827 | Bowles | Stephen | Eastern | - | (one random mark) | Decoration is from the Adams shop, but letterer has yet to be determined |

| 1812 | Bradbury | Thomas | Eastern | E W | - | Footstone only; headstone has not been checked for marks |

| 1798 | Burnham | Abigail | Eastern | - | A, L, P, W | The top of the stone is missing but Bartlett Adams lettered it. |

| 1836 | Burns | Charles Henry & Ellen (1841) | Eastern | - | 2 | A post-Adams stone, broken in at least 3 pieces, shared by 2 siblings Burns Subterranean Celebrity Listing |

| 1814 | Cammett | Sarah | Eastern | E W | Hd | Alvan Washburn’s urn, willow and lettering |

| 1811 | Chamberlain | Martha | Stroudwater | - | (a rustic flower) | Alvan Washburn’s flowered branch and lettering |

| 1800 | Colby | Jonathan Morss | Eastern | - | Noyes | Bartlett Adams's decoration and lettering. Noyes is finely carved. |

| 1816 | Colley | Henry C. | Eastern | W + W | - | Elias Washburn's signature urn and lettering (identical on Jacob Colley stone) |

| 1818 | Colley | Jacob S. | Eastern | W + W | - | Elias Washburn's signature urn and lettering (identical on Henry Colley stone) |

| 1831 | Delano | Joseph | Eastern | - | 49 | - |

| 1845 | Delano | Joanna | Eastern | - | 5 | - |

| 1815 | Dodge | Joseph | Eastern | - | 5 | A Washburn stone with elements that suggest Alvan’s and Elias’s work |

| 1813 | Dodge | Lydia | Eastern | A. W. | $5 Port | Alvan Washburn’s urn and lettering |

| 1812 | Fernald | Elizabeth B. | Eastern | A. W. | 3.50 | Alvan Washburn’s flowered branch and lettering |

| 1813 | Frothingham | shared by 4 siblings | Eastern | A. W. | - | One of 3 marble markers with marks |

| 1820 | Gray | George D. | Eastern | - | $5.75 | Bartlett Adams’s lettering, but artist of the urn is not yet known |

| 1832 | Harmon | Jane Elwell | Woodlawn - Buxton | - | 210 | A stone created by Adams’s successors Francis Ilsley & Joseph Thompson. 210 is centered and neatly carved below the stone’s burial line. |

| 1822 | Haskell | Sarah | Eastern | E. W. | Aug. 24 1815 | Alvan Washburn carved the urn and Bartlett Adams did the lettering. (note misspelling of Portland) |

| 1828 | Hutchins | Benjamin & Nathaniel (1827) | Eastern | - | (many practice marks) | One of 3 marble markers with marks. This is a shared marker for 2 brothers born 1806 & 1810 who died within a year of each other. |

| 1816 | Kimball | Elizabeth | Eastern | E W | - | Fragment was found at Elizabeth Kimball’s plot; reburied at Watts plot. Alvan Washburn’s urn |

| 1830 | Lord | Charles Tebbetts | Eastern | - | 2 | A stone created by Adams’s successors Ilsley & Thompson |

| 1831 | Loring | Lucretia C. | Eastern | - | 2 + 1 | Top 2/3 of the stone is missing |

| 1828 | Martin | Sophia (Leavis) | Eastern | - | 3 10 | Created by Adams’s successor Joseph Thompson. The top line on this marker is for Mary Leavis (died 1802 at age 4), Sophia’s sister. |

| 1805 | Mills | Sally | Eastern | - | Po (probably for Portland; it’s upside down) | One of 3 marble markers found with underground marks |

| 1810 | Montgomery | John II plus 2 infant siblings | Eastern | A. W. | - | Alvan Washburn’s lettering (the top of stone is missing) |

| 1832 | Murch | Sumner Cummings | Eastern | - | (a rustic silhouette?) | A stone created by Adams’s successors Francis Ilsley & Joseph Thompson. The underground portion was finished, not rough |

| 1822 | Page | Theodore | Woodside - Belgrade | - | No 2 | - |

| 1802 | Plumer (Plummer) | Joseph | Eastern | I W | I I | Alpheus Cary’s urn and lettering. The W is unique on this one. |

| 1831 | Poland | Mary Louisa | Eastern | - | 2 + 2 | A post-Adams stone probably done by Joseph Thompson |

| 1815 | Raymond | Elizabeth B. | Eastern | E W | - | Alvan Washburn’s urn and lettering |

| 1819 | Ripley | Thomas | Eastern | W W | - | Footstone only; no headstone is present |

| 1828 | Ruby | William A. | Eastern | - | (some practice marks) | A post-Adams stone. One of 2 stones found within the African American burial patch in Section A |

| 1815 | S. | H. | Eastern | - | (some practice marks) | Footstone only inscribed with H. S. and 1815; no headstone is present and a review of other burial records does not lead to this person’s identity |

| 1818 | Sawyer | Susan | Eastern | W + W | - | Elias Washburn’s signature urn & lettering |

| 1835 | Sigs (Siggs) | Mary | Eastern | - | 2.11 | A post-Adams stone. One of 2 stones found within the African American burial patch |

| 1818 | Tate | Catherine | Stroudwater | I W | x - 5 | Elias Washburn’s signature urn & lettering |

| 1814 | Taylor | Barzillai Delano | Eastern | A. W | - | Alvan Washburn’s urn and lettering |

| 1823 | Thomes | Charity | Stroudwater | I W | - | Bartlett Adams’s lettering, but the artist of the urn is not known |

| 1817 | Walker | Isaac | Eastern | - | 13 3 | Eroding, but appears to be Elias Washburn’s urn |

| 1733 | Walton | Peter | Eastern | - | T | This is a very early stone imported from Boston |

| 1826 | Warren | Huldah Ann | Eastern | - | (a double X or partial hashtag) | The urn and willow design is from the Adams shop, but the carver is not yet known |

| 1813 | Wilson | Susan | Eastern | E W | - | Headstone with Alvan Washburn’s urn and lettering |

| 1813 | Wilson | Susan | Eastern | E W | Por— | Footstone |

| unknown | unknown | unknown | Eastern | - | (many random marks) | fragment |

| unknown | unknown | unknown | Eastern | - | A H J B S W $ & X P E & I I I |

Fragment. These characters appear in relatively straight lines. At least 4 more are also on this piece |

| unknown | unknown | unknown | First Parish - Brunswick | - | Soft Stone A B C D E | This fragment was documented in the 2004 Cheetham survey of the cemetery. |

| unknown | unknown | unknown | Hillside - Yarmouth | - | $11 | This may have come from the Hill family lot just inside and left of the cemetery gate. Fragment. |

References

Description and PDF version: Hidden Figures: Below-Ground Carvings on Gravestones from the Early 1800s

Spirits Alive photo album on Flickr of stones with carver marks and signatures

1 A comprehensive site survey conducted by Donald and Mark Cheetham in 2004 documented these stones, though a walk through the cemetery today reveals that even more have been added along the fence since that survey. back to text 1

2 My stonecutting friend Matt Barnes of Yankee Slate Cutting once told me that pouring fine sand onto the completed inscription surface and gently rubbing with a brick or wood block would have done the trick. back to text 2

3 Trying to determine a current day equivalent for an item’s price 200 years ago is a challenge. Various conversion tables can be found with widely-varying results. back to text 3

4 The fragment was discovered on the Hill family lot by Katie Worthing, Executive Director of the Yarmouth Historical Society. There is a large “billboard” type monument on the lot now, memorializing 10 members of the family. Though the monument is dated 1859, of the 10 died between 1817 and 1820 and Katie believes the fragment is a remnant from an earlier slate that marked one of the graves. That makes sense. Most other stones with hidden figures come from that same general period of time. Individual markers may have been pulled from the lot when the billboard was erected; broken pieces of individual markers can also be seen poking up through the ground. back to text 4

5 During a later stone conservation workshop held at Stroudwater, Janet Alexander worked on her stone and found an “x - 5” carved below the “I W” that I had seen during my visit. back to text 5

6 Researcher Jim Blachowicz covers this part of Bartlett’s life in his 2-volume set entitled From Slate to Marble. back to text 6

7 The stone is inscribed using Plumer, but other records and gravestones for this family use Plummer. back to text 7

8 Alvan’s name and his title of apprentice appear on a bill of sale for a gravestone from Bartlett Adams’s shop that year (documented by Ralph Tucker in the AGS Quarterly, Volume 30, No. 1, published Winter 1996). back to text 8

9 These two daughters, born to Mary (Cammett) Fernald, were named for Anthony Fernald’s first wife, Elizabeth, who passed in 1800. He then married Mary Cammett in 1802. Anthony and his wives tended to name their children for those who had died earlier. Mary’s sons Edwin were born in 1802 and 1804. The first lived just a year while the second survived his childhood. Mary passed in 1815 at 32, and Anthony Fernald married for a third time in 1817. The first daughter born to them was again named Elizabeth (the third). But sadly she too died young. back to text 9

10 I’ve found at least 8 of his markers in the eastern Maine communities of Machias, Lubec and Eastport, four in New Brunswick, and 3 in Nova Scotia. back to text 10

11 There are certainly more from the Noyes family interred there when we include the women who were born a Noyes but took their husbands’ surnames. back to text 11