The Life and Times of Ira Gray: A Portland Barber Who Was Charged with Manslaughter in 1825

Thirteenth in a series of Occasional Papers about Eastern Cemetery in Portland, Maine

by Ron Romano

© March 2024

Figure 0. Ira Gray’s Portland newspaper advertisement that ran for a full year, Fall of 1822 through Fall of 1823

-

Wigs, Scalps, Braids, &c. The subscriber respectfully informs his friends & the public that he sill continues to carry on the Hair Work in all its various branches, at his shop opposite Hay Market Row. Gentlemens' WIGS and SCALPS, Ladies' CURLS and fancy Head DRESSES, furnished at the shortest notice of the best workmanship and on the most responable terms. IRA GRAY. N.B. Cash given for human HAIR. Portland. Oct. 29. tf.

The full life story of Portland resident Ira Gray is simply not known. Many of the genealogical records that are readily available for the white citizens of the town were not created—or were vaguely reported—for Portland’s people of color in the early 1800s. This reality wasn’t limited to Portland, or Maine, or even New England, but existed throughout the United States. Ira Gray was not famous, but as a men’s barber and women’s hairdresser he was likely quite well known in town. His paper trail ended in 1826. Two hundred years later this paper puts him in the spotlight and allows a glimpse at his life’s journey, including an indictment for manslaughter!

Where and when he died isn’t known, so we are left to only wonder if he was laid to rest at Eastern Cemetery. At least three of his children ended up there in the 1820s and it is the single surviving gravestone for his son George that begins to unfold the life story of Ira Gray.

Contents

- George D. Gray (1817 – 1820)

- Ira Gray and Betsey Smith

- The Barber’s Business

- Riot and Homicide

- Ira N. Gray (c. 1814 – 1892)

- Edward J. Gray (c. 1817 – 1887)

- Dancing the Night Away?

- Ira and Betsey’s Other Children

- After Ira Gray’s Acquittal, May 1826

- Betsey Is Found

- A Sidebar: Frederick Joseph

- Wrapping up

- References

This paper includes words describing people of color that are no longer deemed acceptable. The newspaper clippings and historical records are presented here as found in their original sources.

George D. Gray (1817 – 1820)

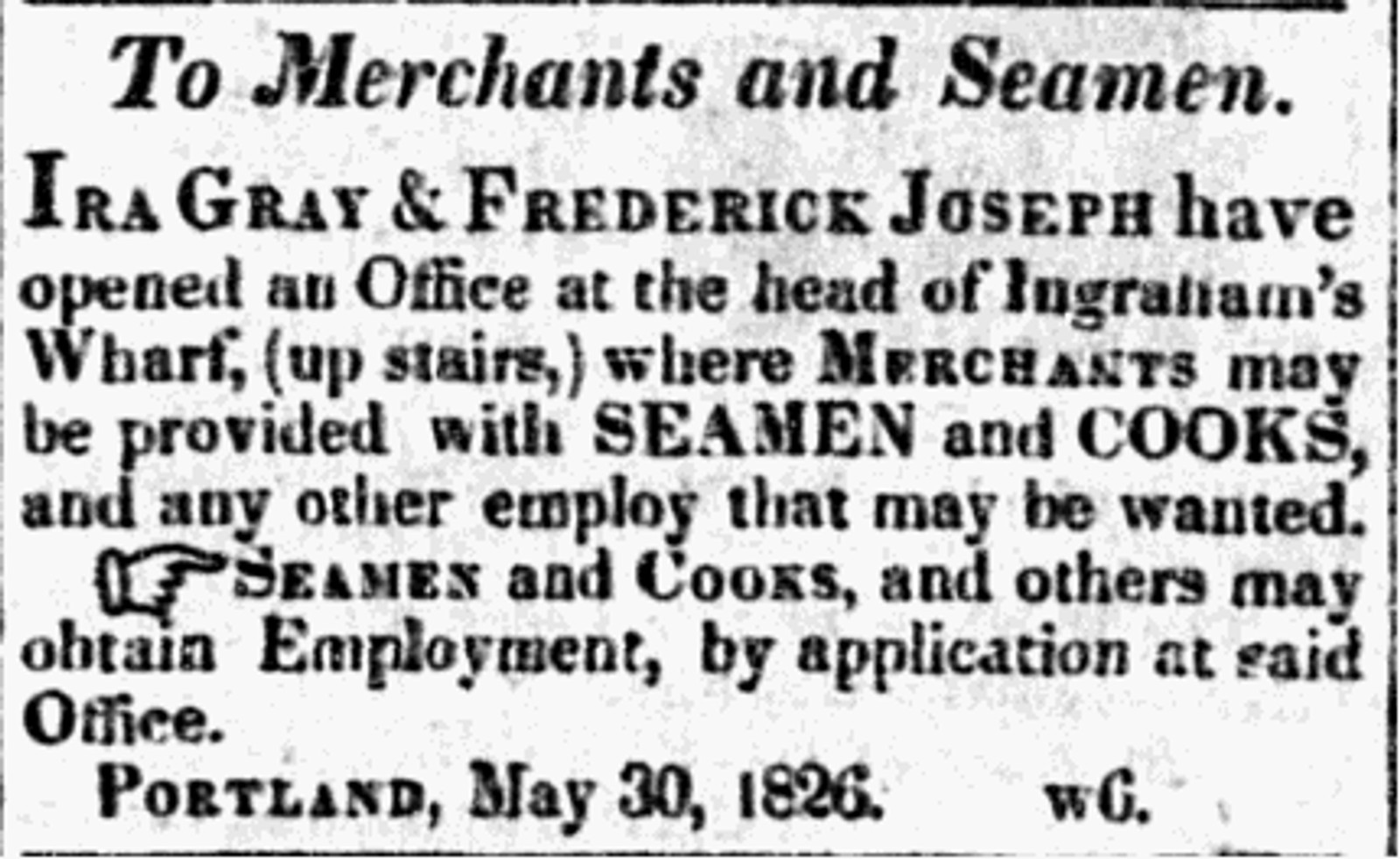

In 2018 the Spirits Alive conservation crew worked on George Gray’s small slate marker. It was found tilting sideways in the back of the cemetery far from the Congress Street gate, and the crew decided to dig it up and set it back upright. George’s stone had been assigned to plot 35A in Section H, a gravesite that does not appear on the cemetery’s first survey map from 1890. Researcher Bill Jordan had conducted his own surveys in the 1970s prior to publishing the book “Burial Records... of Eastern Cemetery...” and it is Jordan who added that plot number to the cemetery’s records.1

Figure 1: George’s gravemarker at Eastern Cemetery.

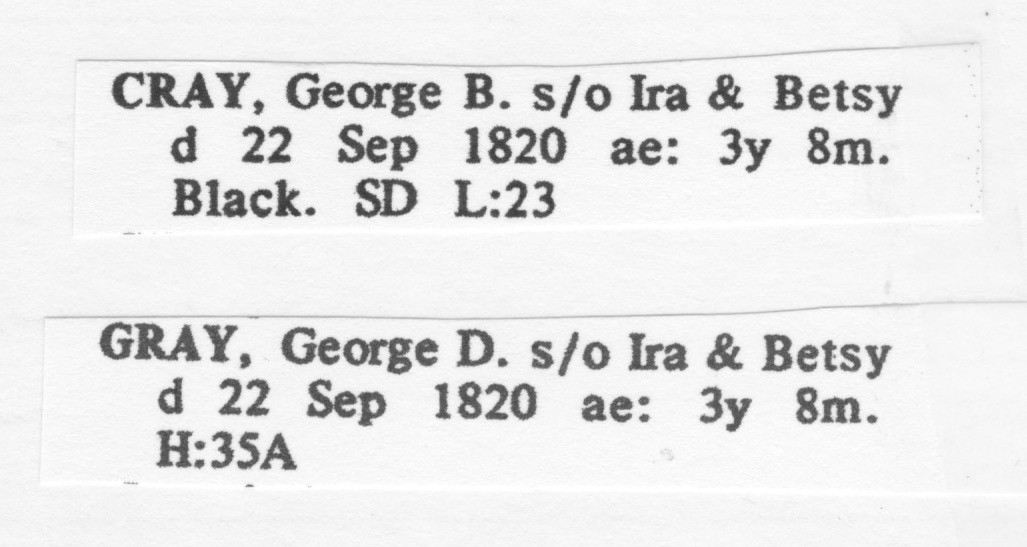

Jordan listed George Gray on page 54 of his book, apparently unaware that he had already accounted for George’s stone on an earlier page under the misspelling of Cray. On page 30 we find that listing, with George’s date of death, age, and parents matching the later listing. The Cray entry is worth noting for a couple of reasons. It gives George’s original plot location (L:23) and confirms that he was Black.

Figure 2: The two listings from Jordan’s book. Plot numbers are at the end of each.

-

CRAY, George B. s/o Ira & Betsy d 22 Sep 1820 ae: 3y 8m. Black. SD L:23 and GRAY, George D. s/o Ira & Betsy d 22 Sep 1820 ae: 3y 8m. H:35A

The 1890 map does have George’s plot L:23. The vital record of his death lists the plot as well, confirming that his stone was there at the time of the 1890 survey. This is important to know because Section H—in the center of the old section of the cemetery—is filled with graves of the white people of Portland, while Section L was reserved for people of color and other minorities such as Catholics, criminals, and paupers. All of this leads me to the conclusion that George’s remains are in Section L even though his stone is no longer there.

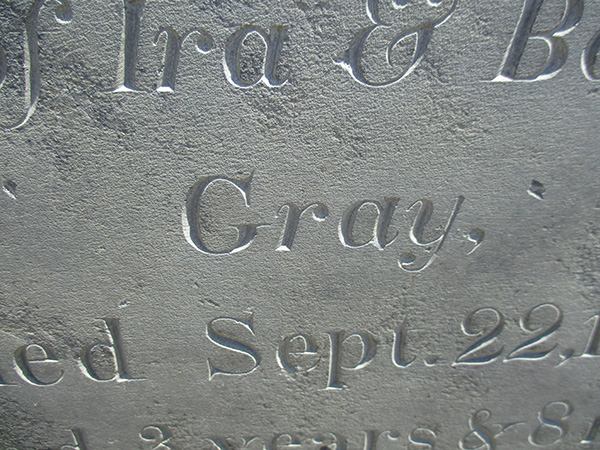

For many years Section L suffered from vandalism. It’s in the far back corner, at the bottom of a steep slope, and in an area out of view from those outside the cemetery fence. I suspect that between 1890 and 1970, George’s stone was dragged around the cemetery by some urchins who left it lying in Section H. Then when Jordan found it, he assumed it belonged where it lay and assigned the new plot number H:35A to the stone. The misspelling of Cray may have contributed to his duplicate listings in the book. It is easy to understand since the chisel stroke across the capital letter “G” in Gray is very lightly done (Figure 3); it takes a close look to see that the letter is actually a “G” and not a “C.”

Figure 3. Close-up of the name Gray on the stone.

George’s stone measures about two feet tall by one foot wide. The urn that decorates the top of the stone was probably carved by Elias Washburn, while the lettering was done by Bartlett Adams. Finding that two men worked on one gravestone in this manner is not at all unusual. The Adams stone shop operated in Portland from 1800 to 1828; Bartlett’s nephew Elias Washburn ran the shop from 1818 to 1821 when his uncle was temporarily living in Boston. Elias was likely creating a supply of decorated-but-uninscribed stones during his stint. Customers could pick the stone design they liked and then have it lettered. When Bartlett returned from Boston there was such a supply of stones that Elias left for him at the shop.

So, I can imagine that in 1821 Ira Gray visited Bartlett’s shop on Federal Street and selected the small marker—decorated with the urn—for his son’s grave. Ira paid Bartlett $5.75 for the stone; the price had been etched onto the bottom of the slate as discovered by the conservation crew in 2018 when the marker was reset.2 Bartlett then lettered George’s stone and had it placed on his grave in section L.

Ira Gray and Betsey Smith

George was one of at least six children of Ira Gray and Elizabeth (Betsey) Smith. They married in Portland in 1810. Their vital record of marriage notes that they were Black, that Ira was from New Haven and Betsey was from Portland. No records of birth have yet been found for Ira and the best we get from his appearance in the 1820 census is a wide, twenty-year birthdate span between 1776 and 1794. I was able to narrow down Betsey’s year of birth to a shorter range of 1794 to 1796 based on census records and her age at the time of her death. Given that she married Ira in 1810, she was certainly a young bride.

The August 1820 census for Portland shows that there were four children under age 10 in their house, three boys and one girl. So Betsey had delivered at least four children before age 25! All were listed as “free colored persons.” George died on September 20, 1820 at the age of 3 years and 8 months, just one month after being included in the census.

At least two more children would join the family after 1820. On September 10, 1822, the Portland Gazette published a simple death notice: “In this town…a child of Mr. Ira Gray.” Because the child was unnamed and lacked sex and age indicators, we can assume that death came shortly after birth. The following September, Betsey delivered a son they named William H. G. Gray. He survived only 28 months. Piecing together the few records found, I know of five boys and one girl born between 1814 and 1823.

The Barber’s Business

Ira’s first known newspaper advertisement appeared five years after he’d married Betsey. In that 1815 ad under the headline “The Barber’s Business” he solicited “a portion of public patronage commensurate with [my] endeavor to please.” At that point he must have been cutting hair only for men. He also offered his clients this: “Gentlemen’s boots and shoes cleaned and polished in the neatest manner.”

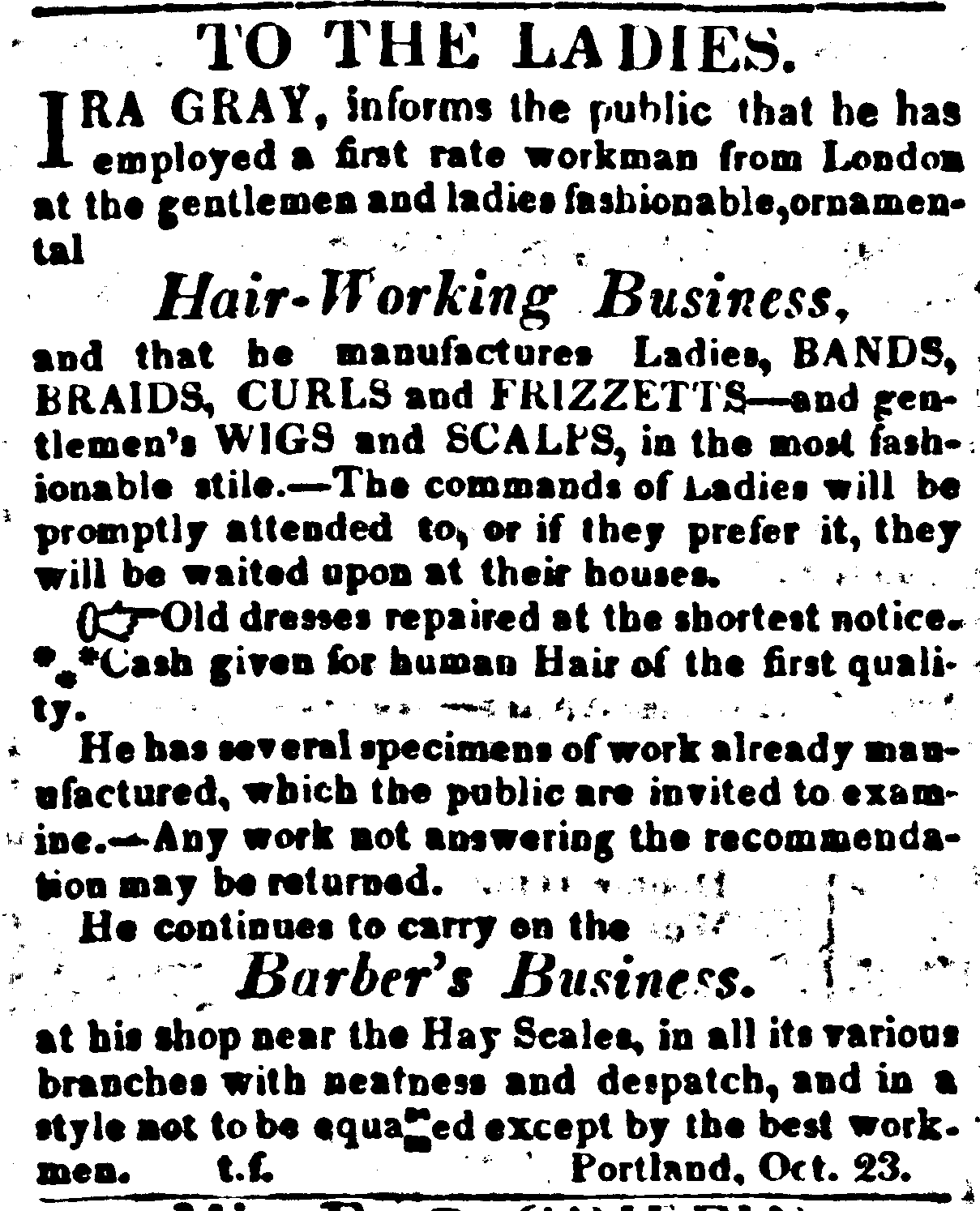

A series of ads beginning October 23, 1821, shows how his business had evolved. Note (Figure 4) the headline “TO THE LADIES” and the ad’s emphasis on women’s hair care.

Figure 4

-

TO THE LADIES. IRA GRAY, informs the public that he has employed a first rate workman from London at the gentlemen and ladies fashionable, ornamental Hair-Working Business, and that he manufactures Ladies, BANDS, BRAIDS, CURLS and FRIZZETTS—and gentlemen's WIGS and SCALPS, in the most fashionable stile. —The commands of Ladies will be promptly attended to, or if they prefer it, they will be waited upon at their houses. Old dresses repaired at the shortest notice. Cash given for human Hair of the first quality. He has several specimens of work already manufactured, which the public are invited to examine. —Any work not answering the recommendation may be returned. He continues to carry on the Barber's Business at his shop near the Hay Scales, in all its various branches with neatness and despatch, and in a style mot to be equated except by the best workmen. t.f. Portland, Oct. 23.

He even offered the repair of dresses, but at the bottom we see that he is still cutting men’s hair too. The first city directory for Portland was published in 1823. Ira was included, listed as a barber with his business on the corner of Congress and Middle Streets and his home on Center Street.

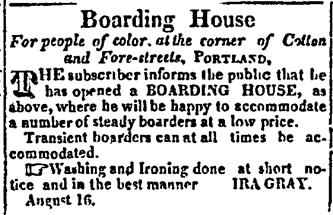

In August of 1825, he may have temporarily pivoted from haircutting to focus on a new venture. As shown here (Figure 5) Ira announced that he had just opened a boarding house for people of color. That ad ran regularly though October.

Figure 5

-

Boarding House

For people of color at the corner of Cotton and Fore-streets, PORTLAND.

THE subscriber informs the public that be has opened a BOARDING HOUSE, as above, where he will be happy to accommodate a number of steady boarders at a low price. Transient boarders can at all times he accommodated. Washing and Ironing done at short notice and in the best manner. IRA GRAY. Angust 16.

Also in October a man named Washington Hall placed a notice in the newspaper that announced he had taken the place “formerly occupied by IRA GRAY…” and that he had opened his own hair dressing business there. Hall’s business didn’t last long. In May of 1826, Washington Hall (noted to be a Black barber in Portland) was convicted of an assault with intent to commit rape. He was sentenced to prison for one month of solitary confinement followed by five years of hard labor.

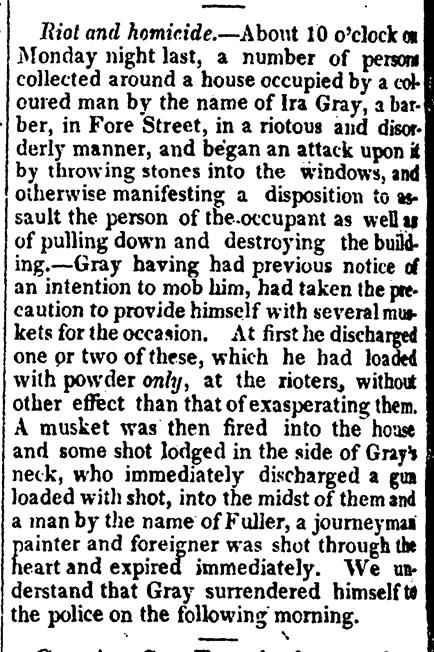

Riot and Homicide

On November 7, 1825, Ira’s family experienced a terrifying night. The newspaper account of the incident tells the story best.

Figure 6

-

Riot and homicide.—About 10 o'clock on Monday night last, a number of persons collected around a house occupied by a coloured man by the name of Ira Gray, a barber, in Fore Street, in a riotous and disorderly manner, and began an attack upon it by throwing stones into the windows, and otherwise manifesting a disposition to assault the person of the occupant as well as of pulling down and destroying the building.Gray having had previous notice of an intention to mob him, had taken the precaution to provide himself with several muskets for the occasion. At first he discharged one or two of these, which he had loaded with powder only, at the rioters, without other effect than that of exasperating them. A musket was then fired into the house and some shot lodged in the side of Gray's neck, who immediately discharged a gun loaded with shot, into the midst of them and a man by the name of Fuller, a journeyman painter and foreigner was shot through the heart and expired immediately. We understand that Gray surrendered himself to the police on the following morning.

Apparently this attack on his family and home did not come as a surprise since Ira had somehow received advance notice of the perpetrators’ plans. What was this about? I jump to the thought that this must have been a racially-motivated incident, but perhaps it was something else. Whatever the cause, it left Ira with a bullet wound to his neck and a man lying dead outside his home. A lesser man might have taken his family and fled from town, but Ira Gray instead took the higher road and—quite bravely, I think—surrendered to the police. He was charged with manslaughter in the death of Thomas J. Fuller. Did he spend time in jail? It’s not clear. During March of 1826, in the post office’s regular notice of letters being held and available for retrieval, we find Ira Gray’s name. Maybe he was in confinement, or maybe he just had mail that he hadn’t picked up. Then in April he announced that he had opened a new barber shop. This suggests that his decision to turn himself into the police may have given him enough credibility so as to allow him to walk free while awaiting trial.

There’s a poignancy to that April advertisement. At the bottom of the ad we find this line: “[Ira Gray is] grateful for the encouragement he has heretofore received, and solicits a share of patronage in the future.” It seems his neighbors and customers had not shunned or abandoned him during this ordeal; instead, they seem to have supported him when he needed it the most.

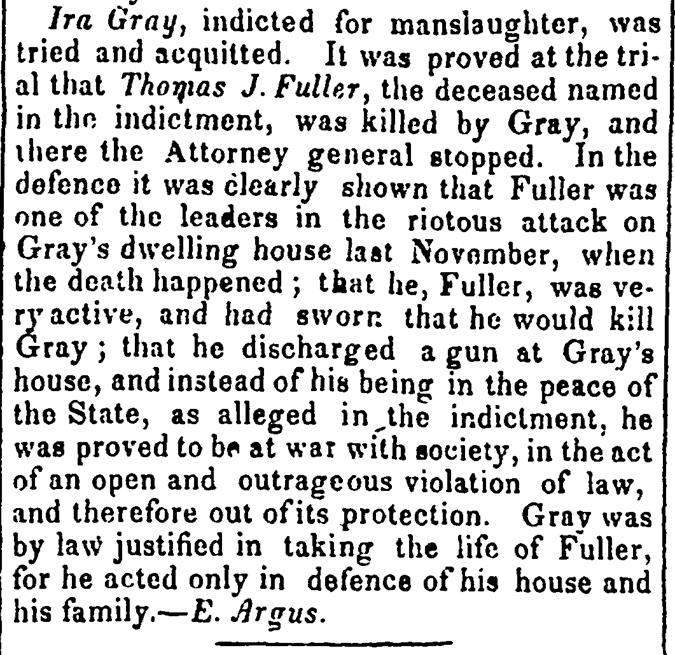

His trial took place in mid-May. Once again, the newspaper tells the story best.

Figure 7

-

Ira Gray, indicted for manslaughter, was tried and acquitted. It was proved at the trial that Thomas J. Fuller, the deceased named in the indictment, was killed by Gray, and there the Attorney general stopped. In the defence it was clearly shown that Fuller was one of the leaders in the riotous attack on Gray's dwelling house last November, when the death happened; that he, Fuller, was very active, and had sworn that he would kill Gray; that he discharged a gun at Gray's house, and instead of his being in the peace of the State, as alleged in the indictment, he was proved to be at war with society, in the act of an open and outrageous violation of law, and therefore out of its protection. Gray was by law justified in taking the life of Fuller, for he acted only in defence of his house and his family.—E. Argus.

Thankfully, there was a positive outcome for Ira Gray to what certainly must have been a challenging six months.

Ira N. Gray (c. 1814 – 1892)

At the beginning of this paper we met George (1817 – 1820), the second of the six children I have documented in the family. The first in line was Ira’s namesake son, with the added middle initial of “N.” No vital record of birth has been found, but other records help tell his story. Ira Jr. is accounted for in the 1820 US census for Portland as one of the boys born before 1820. Two records are found related to his marriage in Boston in 1842. His bride was Louisa E. Nell. One of the records is the 1841 intention of marriage and beside Louisa’s name is a parenthetical note reading “Col ?” The second record is from April 1842 and the note beside Louisa’s name is “(col’d).” These are references to her race, both being short for “colored.”

In the 1855 Massachusetts census, Ira and Louisa are named along with a 12-year-old son. Ira was working as a waiter; his race was listed as mulatto. I could find no other records for Ira and Louisa until the 1880 US census for Boston. Oddly, Ira was listed as a white male. He was age 70 and still working—as a caterer. Louisa was listed as a white female, age 58, who was keeping house. The references to their race are incorrect, but all other indicators are a good match, so I am confident this census record is for our Ira.

Ira was listed in the 1892 Boston directory as boarding at the home of his late brother Edward. Then in the 1893 directory there is a note that reads “Ira N. Gray died Nov. 24, 1892.” His vital record of death confirms that he was the child of Ira and Betsey (Smith) Gray, that he was born in Portland in 1814, and that he was a cook. His cause of death was heart disease and his age at the time of death was 78. No burial location was indicated on that record and no listing is found for him today on the Find A Grave.com website.

Edward J. Gray (c. 1817 – 1887)

Available records suggest that Edward J. Gray was third in line (behind Ira and George). He lived a long life to age 70. Like his brother Ira, he died of heart disease. He had been the owner of a house at 25 Newland Street in Boston for over 30 years and as noted above his brother Ira was living in that house when he died in 1892. Edward’s vital record of death, like Ira’s, confirmed him to be the son of Ira and Betsey Gray. He was noted to be “colored.”

Edward appears in four consecutive federal censuses in Boston—1850, 1860, 1870, and 1880 —but Boston directories suggest he may have been there as early as 1834 (at age 17). On all of the census records his occupation is consistent: he was a barber just like his father. What is not consistent is his race. He was listed as “Black” in 1850, “Mulatto” in 1860, “White” in 1870, and “Mulatto” in 1880. Edward married Mary J. Gregory in 1843 and they had at least seven children between 1844 and 1864, all of whom are well documented in the census records.

Figure 8

-

Married, In this city, January 23, by the Rev. T. M. Clark, Mr. Edward Gray to Miss Mary J. Gregory. January 26, Mr. Thomas Bacall to Miss Elizabeth D. Mills.

Records for Edward are the most complete for this family. But there’s one problem to be reconciled between brothers Edward and George. They are definitely both the children of Ira and Betsey—confirmed on Edward’s 1887 death record and on George’s 1820 gravestone—but neither has a vital record of birth. When I calculated birth dates, I ran into something that doesn’t make sense. George’s gravestone notes he died on September 22, 1820, at age 3 years and 8 months; his calculated birth is therefore January 1817. Edward’s death record notes he died on March 21, 1887, at age 69 years, 11 months and 21 days; his calculated birth is March 1817, two months after George. There is a record error somewhere here.

Dancing the Night Away?

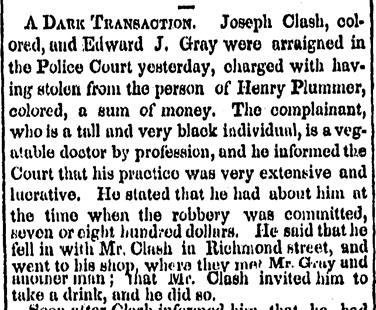

In almost all of the official records, Edward was named as Edward J. Gray. While researching the family for this paper, I scoured the 1800s newspapers from Maine and Massachusetts looking for details. There were other Edward Grays in Boston at the time ours lived there—a captain, a doctor, a lawyer, and even a schooner named Edward Gray—so dozens upon dozens of clippings exist. I found a series of notices from the 1840s and 1850s of a Black man in Boston named Edward Gray (no middle initial) who was arrested for assault, robbery, keeping a house of “ill fame,” selling liquor without a license, and domestic disturbances. Then in July of 1853 there was another incident reported, this time involving “Edward J. Gray.” Under a title that I suggest was intentionally written to have a double meaning (Figure 9), Edward was implicated in a robbery. The rest of the story is that Mr. Plummer accused the men of giving him a drink that was laced with something that left him unconscious, and when he awoke he found his money was missing from his pocket.

Figure 9: The first paragraph in a larger article from the July 1, 1853 edition of the Boston Herald.

-

A DARK TRANSACTION. Joseph Clash, colored, and Edward J. Gray were arraigned in the Police Court yesterday, charged with having stolen from the person of Henry Plummer, colored, a sum of money. The complainant, who is a tall and very black individual, is a vegatable doctor by profession, and he informed the Court that his practice was very extensive and lucrative. He stated that he had about him at the time when the robbery was committed, seven or eight hundred dollars. He said that he fell in with Mr. Clash in Richmond street, and went to his shop, where they met Mr. Gray und another man; that Mr. Clash invited him to take a drink, and he did so.

Figure 10: Another article from the Boston Herald, June 30, 1853.

-

NOT TO BE MISTAKEN. The "Edward Gray" arrested with Joseph Clush, on a charge of robbery in Ann street, is not the Edward S. Gray, of No. 1 North Square, who is a barber during the day, and the popular fancy dancer in "Uncle Tom's Cabin," at the Museum, in the evening.

I do not think our Edward was the scoundrel who was responsible for the other crimes noted above, but this one is a possibility. We learn from related articles that this Edward was Black and was a barber. Our Edward was a small business owner at the time and had a wife and three children to care for, so I hope his path was a straight and narrow one.

There was a second series of articles in Boston papers in 1847 and 1848 about an African American named Edward Gray. He was also known as the “Boston Rattler,” a very popular dancer whose performances were taking Boston by storm. He thrilled his audiences; one article said the he was the “best negro dancer now living;” another said he was the best dancer to ever have visited Boston (emphasis added). My assumption was that this was not our Edward since ours wasn’t visiting town—he lived there.

Apparently the people of Boston had as much trouble as I’ve had sorting out the Edward Grays of the time. While intending to clear up some confusion, the article above entitled “Not to be Mistaken” just further muddies the water. It doesn’t mention an Edward J. Gray at all. But it says that Edward “S.” Gray (not arrested) was a barber AND the famous dancer.

In the end, the charges against this Edward Gray for the robbery of Mr. Plummer were dropped.

Ira and Betsey’s Other Children

From the available records, it appears that only two children, Ira N. and Edward J., survived their childhoods. George had died at age three. Another sibling died in September of 1822. This child was unnamed in the newspaper and was not listed as a son or daughter, suggesting that the child died during childbirth or very shortly after.

The 1820 census accounted for four children under age ten, three boys (Ira, George, and Edward) and one girl. Unfortunately, since I have been unable to find a census for 1830 for the family, I have not been able to identify her or track her life. There is a small chance that she was the unnamed child who died in September of 1822 noted just above. But I’d expect a child of age two or three would have been named in the paper. So, for now, this girl remains a mystery.

The last of George’s known siblings is William H. G. Gray, who was born in May of 1823 and died in September of 1825. It’s a big name for a little boy, and it got me diving down another rabbit hole to figure it out. But it wasn’t a deep dive. In December of 1822, a man named William H. G. Johnson began a series of newspaper ads regarding his business as a barber and manufacturer of gentlemen's wigs and “sculcaps” (toupees) and ladies’ head dresses. His ads were filled with flowery language. Among the best lines, always expressed in the third person point of view, are these:

He would likewise inform those who honor him with their custom, that he has employed a first-rate workman, to divest boots and shoes of their dirt, and will give them [polish] equal if not superior to the London touch, which will be done at the same time he is decorating the more noble part of man, the head, and thereby cause no delay in his customers’ business (from December 1822)

Ever alive to the interest and convenience of his numerous and respectable patrons, who have been so long been encircled in “The broad banner of his love”—he has been moved by “the celestial fire of his profession” to engage an East Indian of unrivaled skill in the art or mastery of Shaving... (from February 1823)

It’s clear that Ira Gray and William H. G. Johnson were well acquainted and their friendship led Ira and Betsey in May of 1823 to name their newborn son after him.

After Ira Gray’s Acquittal, May 1826

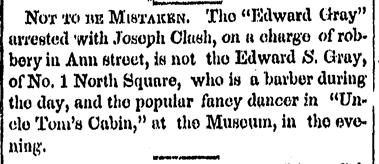

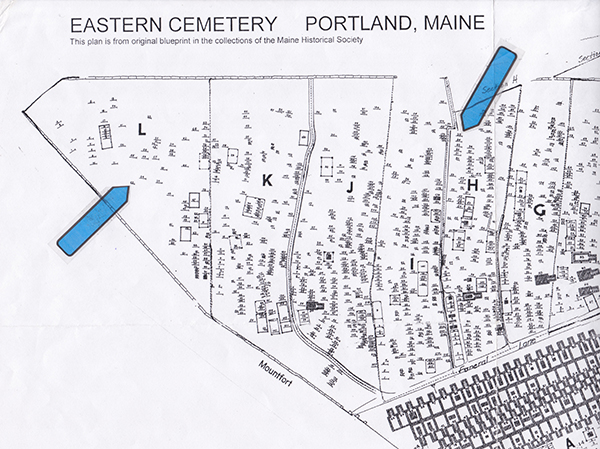

Within a couple of weeks of the acquittal in his manslaughter trial, Ira Gray picked himself up and dusted himself off. He ran one more series of advertisements in the newspaper that reflected another career pivot (or perhaps a sideline business). This ad (Figure 11), with new business partner Frederick Joseph, ran in newspapers in June and July of 1826, then ended.

In fact, no more advertisements are found for Ira Gray after this one.

Figure 11: Another article from the Boston Herald, June 30, 1853.

-

To Merchants and Seamen. IRA GRAY & FREDERICK JOSEPH have opened an Office at the head of Ingraham's Wharf, (up stairs,) where MERCHANTS may be provided with SEAMEN and COOKS, and any other employ that may be wanted. SEAMEN and Cooks, and others may obtain Employment, by application at said Office. PORTLAND, May 30, 1826. w6.

The second directory for Portland was published in 1827, four years after the first in which Ira’s name had been included. For the 1827 edition neither Ira nor anyone else in his family was listed. Had they moved away? I couldn’t find an 1830 or even an 1840 US census anywhere for Ira or Betsey. Had Ira died in Portland shortly after his trial? This seems to me to be the most likely of the options, especially since all newspaper advertising had come to an end. It was not unusual for a widow to be named in a directory when she was the head of a household. Betsey wasn’t listed. If Ira had died, she may have moved into someone else’s home in Portland and therefore just got lost from the records for a while. But for Ira Gray, the paper trail ended in the summer of 1826.

Betsey Is Found

Betsey’s paper trail had lapsed—not ended—as I found her living in Boston in 1850 (with no husband) in the large household of a 103-year-old woman named Catherine whose surname appears to be “Boston.” In this home were a couple named Green in their seventies, then Betsey Gray at age 54 and six other people named Gray from ages 7 through 23 (one named Ira was age 8). Rounding out the eleven occupants of the house was a laborer named Caldwell. All in this home were Black.

By 1860, Betsey had moved into her son Edward’s home at 25 Newland Street, which he had owned for a few years. In this census Betsey was listed as a widow of the mulatto race and age 66. Ten years later she was still living with Edward and his family on Newland St. In that 1870 census she was age 75 and listed as white. Betsey died in Boston on January 26, 1878. She was 82, noted to have had brain disease for years and an onset of paralysis just three days before death. Her vital record named her father Peter Smith and her mother Mary (who was an English immigrant). Betsey, who had never remarried, was laid to rest at Forest Hills Cemetery in Jamaica Plain, just outside of Boston.

Find A Grave.com is a crowd-sourced website that includes millions of cemetery listings. No listings were found for Ira or Betsey Gray, and only two records for their children—George at Eastern Cemetery in Portland and Edward at Forest Hills. As a result of the details found in Betsey’s death record, I created a listing for her at Forest Hills and connected her to Edward. I then connected George with them both. Finally, based on the death notices for her unnamed child from 1822 and son William H. G., I created listings for them at Eastern Cemetery, the only option for burial in Portland at the time. I connected them to Betsey and their brothers. I suspect that Ira N., who died in Boston after his brother and mother, was probably laid to rest at Forest Hills in Jamaica Plan with them.

A Sidebar: Frederick Joseph

Frederick Joseph had something in common with Ira Gray beyond being a man of color. Frederick had been the victim of an assault in Boston just a few months before Ira was attacked in Portland. The paper reported that a sailor, Jesse Bates, had begun a “most ungentlemanly attack” on Mr. Joseph’s home. Bates threw stones and bricks, breaking windows and swearing that he would “whip all the negroes” inside. While defending Frederick Joseph in their report, the newspaper’s racist slant was evident. It noted Mr. Joseph to be “a respectable, discreet, and prudent man, notwithstanding the unfashionable hue of his complexion…”

Bates was arrested in the midst of the unprovoked assault. In court he asked the judge for mercy, stating that he was a poor fisherman, near sixty years of age, and unaware that Boston’s intoxication laws were so strict. He told the judge he would only get worse in prison and that he would instead do his drinking "in the bushes" where he would not disturb anyone. He further expressed his view that all Black people should be sent south.

The judge fined him $3 and the costs of prosecution. He should have made Bates pay for repairs to Frederick Joseph’s home...

Wrapping up

The lives of Ira Gray, Betsey Smith and their children are limited in detail. They were never famous and probably never wealthy. Of the core group of eight, only three lived long lives. These were ordinary people, but Ira especially touched the lives of many others in Portland in the early nineteenth century. Beyond his service as a barber, his efforts to establish a boarding house and employment agency for Portland’s minority people proves his commitment to bettering the lives of others. Ira’s experience defending his family during the assault—only to then face a manslaughter charge—must have taken a toll on them all, but he persevered. The lack of vital records leaves some questions unanswered, especially Ira’s date and place of death. So, rest in peace, Ira Gray, wherever it is you lie.

Figure 12: Map shows George’s gravesite (Section L, plot 23) and the location of his stone (Section H, plot 35A). The Spirits Alive conservation team will consider whether or not to move George’s stone.

THE END

References

Description and PDF version: The Life and Times of Ira Gray: A Portland Barber Who Was Charged with Manslaughter in 1825

1 Burial Records, 1717–1962 of the Eastern Cemetery Portland, Maine was published in 2009 by Heritage Books, Inc., Westminster, MD. back to text 1

2 See my 2023 paper entitled “Hidden Figures: Below-ground Carvings on Gravestones from the Early 1800s” for more information. back to text 2